Generator, innovator

Growing Greener Innovations brings greener energy to the world

Connie Stacey is not one to shy away from a challenge.

In 2014, she set an ambitious goal. After 20 years working in IT, she wanted to make a change. She wanted to enter the world of entrepreneurship. And she wanted to find a way to provide power to billions of people around the world.

She wanted to solve energy poverty.

Over the past six years, Stacey has made some major strides towards this goal. She has learned the ins and outs of how batteries work. She’s brought game-changing ideas to market. And developed relationships with clients and partners around the world, from Peru to India, Singapore and the Philippines.

It’s hard to believe her growing infuence all started with a single noisy generator.

“I was off for a walk with my twin boys — they were about three months old — and I went by a house being built that had a diesel generator running,” she says. “And I thought, if you wake these babies, I swear, I am going to lose it.’”

The moment stuck with her, well after she returned from the walk. She started thinking about generators, and energy in general.

“I started thinking to myself, why do we use diesel generators? They’re the worst. They’re horrible on the environment, they’re loud, they’re expensive, everybody hates them, they’re a must, not a nice to have,” she says.

Although she didn’t have experience in the energy sector, or with batteries, Stacey did have two decades of experience in IT. She also had a general understanding of electrical and computer components. And most importantly, she had a desire to make change.

“I researched it for a good while and I learned more about batteries and I kind of had this thing where every single day I had to do one thing towards making this product come to life,” she says.

About 15 months later, she came across the concept of energy poverty – the concept of large parts of the global population not having enough power to light or heat their homes. It affected nutrition, health, and even safety.

The statistics she learned were startling.First, that there are about one billion people in the world who have zero access to energy.

“They’re candlelight only. That’s one in eight people. That’s astounding,” she says.

Second, that there are 2.6 billion people who don’t have enough energy to cook in any way other than to burn something.

“For a lot of them it’s open fire, it could be garbage, it could be debris, it could be just about anything,” she says. “And the offshoot of that is that it’s one of the biggest causes of acute lung disease and illness in the world.”

And third, about half the world’s population lives in what is called ‘domestic energy poverty,’ which, she explains, is where people either have consistent, low-voltage power, or only have power for certain hours of the day along with rampant blackouts.

“Where we are, especially in Alberta, we are so privileged in terms of our energy. It’s like a non-issue here,” she says. “So when I learned this I thought, wow, okay, what I’m building has a potential not to just be a good business. This could change the world for people who are living in poverty.”

As she learned more about the impacts of energy poverty, and its negative correlation with economic growth, she grew more determined.

“And that’s when I said, ‘You know what? I’m gonna do this,’” she says.

Since then, Stacey has learned the minutiae of batteries. She understands not only how they operate in general, but the features that make them sustainable or not. She’s uncovered ways to make them more environmentally friendly, to reduce waste, and make them more practical in extreme conditions.

She started by addressing the conditions that would be the hardest on temporary power sources. Two of the most extreme options she could think of were a community in

Northern Canada, with no other access to power, and a rural village in sub-saharan Africa. She wanted to create a power source that had three broad features: it had to be simple and easy to use – so you didn’t need to be an electrician to operate it; it had to be portable so it could be used in remote areas; and it had to be scalable in order to answer varying needs.

The resulting products, the Grengine solar battery generator and folding solar panel are Stacey’s first major milestones along the path to solving energy poverty. And while she knows the goal of ending global energy poverty is a way’s off yet, Stacey is determined.

The generator is what Stacey calls input agnostic, meaning it can be powered by a range of different power sources, be it solar energy, or lithium ion, or solid-state lithium batteries. What’s more, the generator has undergone extensive field testing done with the Department of National Defense to highlight the practicality and efficiency of using different the power sources.

“It works seamlessly,” she says. “So the idea is when the next new battery chemistry comes out, you don’t have to start from scratch, you just keep building onto it, you only replace that which needs to be replaced.”

But the Grengine and folding solar panel are just the first steps in Stacey’s path to ending energy poverty.

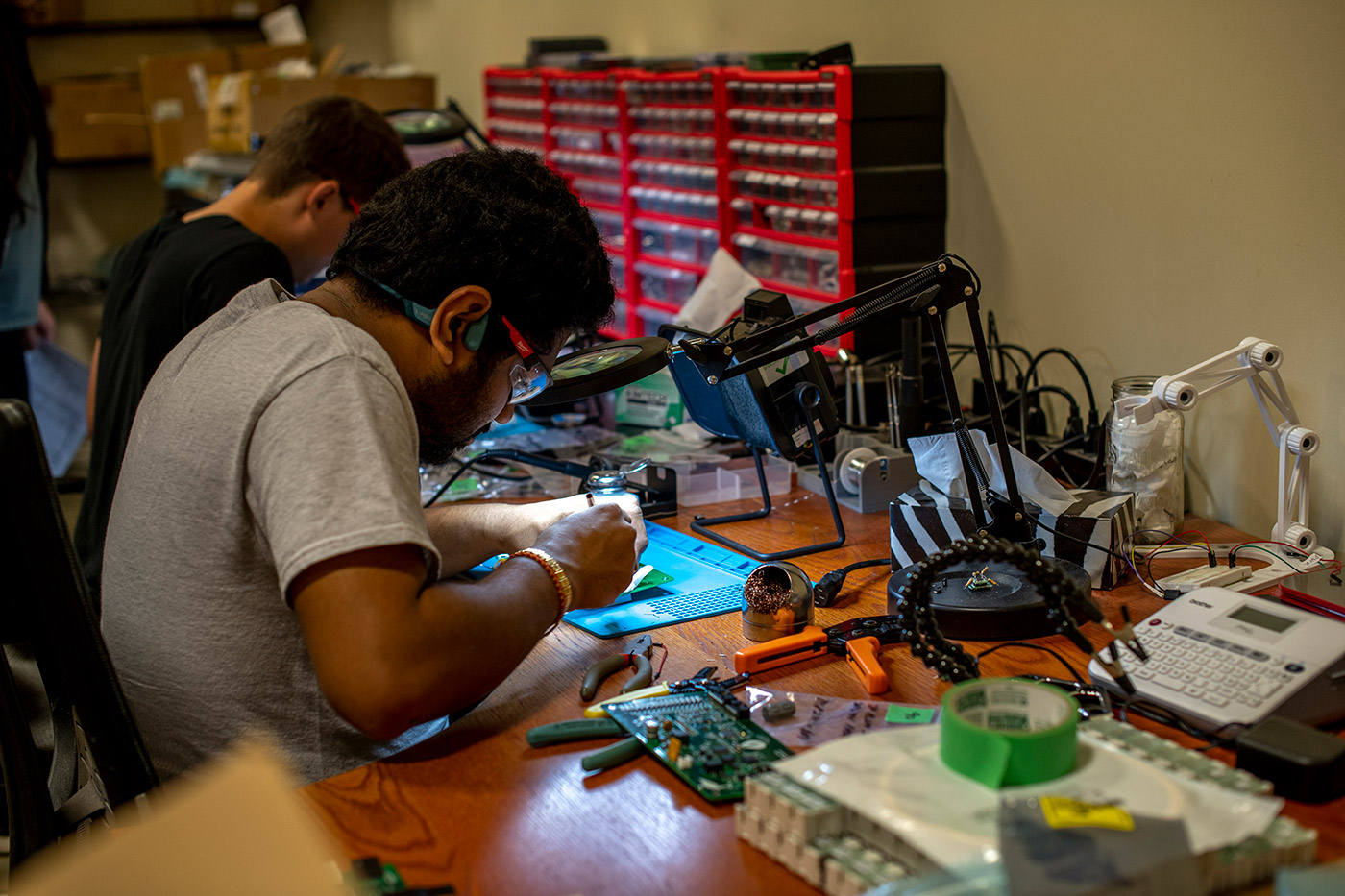

As the groundwork comes together for Growing Greener Innvation’s Edmonton production facility, Stacey sees it as another win. Her goal is to develop roboticized manufacturing facilities that can be built in markets around the world in order to answer worldwide energy needs. By using roboticized manufacturing, Stacey aims to reduce the ecological impact of shipping and producing components worldwide.

“Well think about the footprint that your average battery has in going around the world as it’s produced,” she says .”We wouldn’t even ship from Canada ‘cause the environmental footprint just wouldn’t make sense”

As demand grows around the world, Stacey hopes Growing Greener will be able to build its production capacity with regional facilities.

But first, she wants to get the groundwork right. With construction underway on the Edmonton facility – thanks in part to Growing Greener’s relationship with SEF – Stacey’s looking forward to ramping up production. She expects the facility to be operational by mid-2023. In the meantime, she’ll keep pushing towards her goal of ending energy poverty. One meticulously researched step at a time.

“So stay tuned,” she laughs.

After thirteen years in the Executive Director chair at SEF, it is time for me to move on.

Every day SEF works with entrepreneurs—non-profits, for-profits, cooperatives – determined to find a better way to do things, to create a sustainable economy leading to a more inclusive community that works for everybody.